Project Description

#TellMeYourBreraStory

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, 2013-2014

Being taken by the hand and guided by the stories of men and women […] is an eye-opening experience, showing us how the first, essential vehicle for a journey through the museum is not so much expert knowledge, as open eyes, mind and heart

Emanuela Daffra, art historian and museum curator

As in the case of “Brera: another story”, the choice at the heart of #TellMeYourBreraStory is to adopt storytelling as a powerful vehicle to help all visitors approach artworks in a way that resonates with their own lives, regardless of their prior knowledge or cultural consumption patterns.

The new project takes stock of the lessons learned from “Brera: another story”, shifting its focus on workforce development, and enriching the interpretation and mediation skills of nine museum educators.

Archive photo

Each one of them engaged in a dialogue with an artwork of his/her own choice, not only from an art-historical point of view (as it normally happens in their day-to-day activities), but also from a personal and emotional perspective. For this to happen, it was necessary to start working on the storytellers’ individual sensibilities, on expanding their ability (and willingness) to bring their life experiences to the surface, before approaching the artwork also from a “scientific” point of view, and starting to interweave the two dimensions.

The resulting narrative trails were addressed to small groups of adult visitors, personally guided by storytellers through the exhibition spaces. Short texts, images or video clips were posted on the museum’s social media so as to raise expectations in the audience, to invite people to take part in the trails, but also to encourage them to share impressions, emotions, memories triggered by the visit.

#TellMeYourBreraStory is a project curated by Emanuela Daffra and Paola Strada (Brera Education Services) in collaboration with Silvia Mascheroni, Maria Grazia Panigada and Simona Bodo.

The integral texts of the stories are published in S. Bodo, S. Mascheroni, M. G. Panigada (eds.), Un patrimonio di storie. La narrazione nei musei, una risorsa per la cittadinanza culturale (Mimesis Edizioni, 2016).

Watch the trailer of #TellMeYourBreraStory (Pinacoteca di Brera – a Storyville production)

Watch the video clip of Eva Susner in dialogue with the Pietà by Giovanni Bellini

Watch the video clip of Rosi Gradante in dialogue with the Polittico di Cagli by Niccolò di Liberatore and Pietro Mazzaforte

Watch the video clip of Emanuela Rita Spinelli in dialogue with the Nativity of Mary by Gaudenzio Ferrari

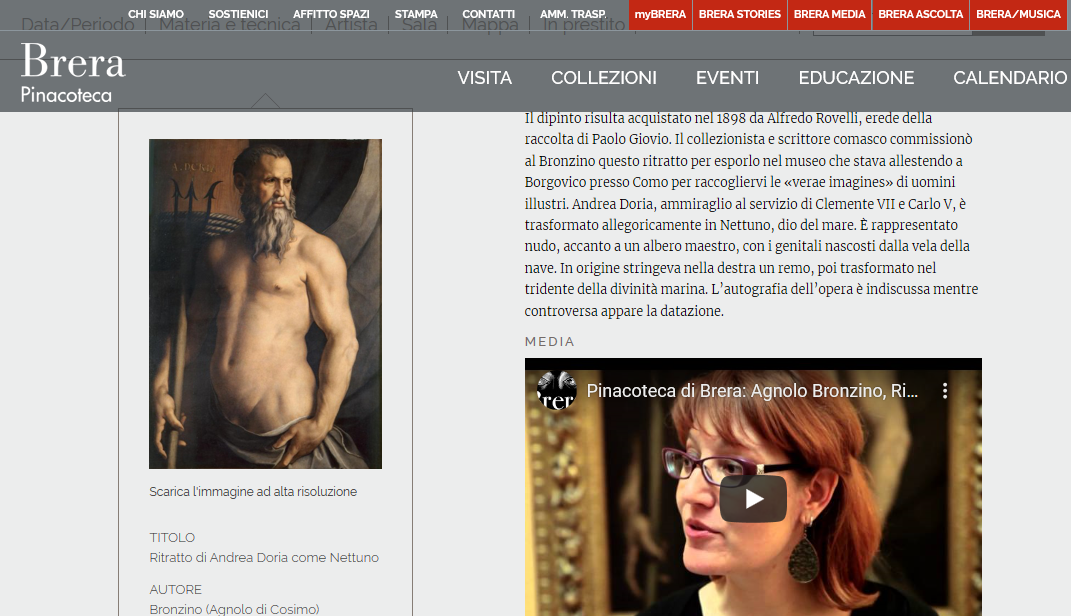

Watch the video clip of Silvia Mausoli in dialogue with Andrea Doria portrayed as Neptune by Agnolo Bronzino

Watch the video clip of Ivana Santarsiere in dialogue with the Odalisque by Francesco Hayez

Extracts

We are here.

I am here.

Standing upright, in front of these three life-sized figures.

The space of a balustrade between us, just enough to keep a safe distance.I can see them clearly, very clearly, I can count every single hair Giovanni Bellini painted for Apostle John, here, on the right; if I want to, I can make out the tiny brush strokes filling Jesus’ arm, his skin, with muscles, tendons, bones, veins, and blood. Blood flowing back towards the elbow, blood weighing in the veins, weighing in the hand.

I can see the landscape, which in no way recalls Giovanni Bellini’s Venice, not its sounds, not its colours; and it is not Padua either, not its hills. The sky, perhaps…But my gaze always, inevitably, stops there, where the two profiles draw near, where the two faces move closer. And there is no more landscape, no more Apostle John, no more distance. Only a mother waiting, looking for a breath.

I am asking you to make an effort. Just envisage this space empty, only filled with light, gold, and this meadow.

For late-Gothic artists, painting a meadow for the feet of the saints to rest on amounted to representing the Garden of Eden. And so it was for Niccolò.

It smells like an alpine meadow, created with thick, masterly brush strokes.

And yet, light is the real protagonist; not the blades of grass, not the flowers. The pale green in the foreground slowly becomes darker and darker as one enters. Here’s depth, here’s perspective!I have a meadow too. A garden. It surrounds my house. I chose that house because it had a garden. An imaginary garden, because in the beginning there was nothing there… just soil.

I moved away from my family to have it. The house is small. I had to get rid of many things, I had to make room, I had to create a vacuum.

I walk through these rooms every day, to the point that I no longer see the paintings…

All but one, the one I always notice. I can feel its presence, and every time I stop to look at it. […] I stop and look, as if to check everything is in its place, as if to make sure nothing has moved, and I look at it because … in some way I am attracted by this body, the naked body of a strong, muscular man, taking up the whole surface of the painting. […] I see a man of the sea.But if my eyes dwell on his hands, there is something inconsistent with what I have always noticed in sailors: his gestures, so delicate and graceful, almost womanly; his nails, so clean and neat; his skin, which looks more familiar with moisturising creams than with the rough, harsh matter of the ropes.

I have seen the hands of the seamen or, as we called them in Gaeta, the “embarked”. The hands of uncles, neighbours – strong, hard, callous. Hands moving without hesitation. Hands working tirelessly to prepare the mid-August festivity of the Madonna di Porto Salvo, the Protector of sailors.

Shyly and yet confidently, Carolina lets the painter look at her; Francesco aims at the essence of her beauty, without affectation or frills: a natural, warm look; an unfathomable, melancholy expression.

Confidently and yet with a slight unease, we let our loved ones look at us. Sitting on the lawn, in a park, this suddenly turns into a game: I tie my hair up, and arrange the blanket around my head. Everything else comes naturally: I hold it firmly around my arm and waist; the other hand, almost instinctively, conceals the breast. Shyness does the rest; I tilt my head, look away and stop talking.

Photo by Maria Grazia Panigada

Photo by Maria Grazia Panigada

Photo by Simona Bodo